|

Beyond the Crisis: Background Briefing from Berlin

The head of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, has called for Europe’s leaders and citizens to take “a brave leap of political imagination” toward completing the historic project of integration by moving toward a federal political union that will unify Europe in an increasingly competitive global economy.

EU Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso has also recently said “we will need to move towards a federation of nation states. That is what we need. This is our political horizon.” In its September report, the Future of Europe Group, headed by German foreign minister Guido Westerwelle and signed by 11 EU member states, has called for a more fast-paced move toward greater integration of Europe.

So far, however, there has been little systematic public debate about what such a political union might actually look like—whether it encompasses all 27 members or a more core group of states—and how, in practical steps, to get there from here.

To help foster this debate the Berggruen Institute on Governance has compiled an inventory of some the key ideas proposed—and questions raised—about the future of Europe’s governing institutions.

WHAT POLITICAL UNION MIGHT LOOK LIKE | As Jürgen Habermas has correctly pointed out, if the political institutions of Europe that share sovereignty are to be democratically legitimate, they will have to find the right balance between “European citizens” and the “nation state.” All proposals envision the European Commission as the executive power, but there are alternative ideas as to how to lend further legitimacy to the Commission and balance it’s power with the Parliament, which represent the citizenry, and the Council, which represents the nation-states.

The main proposals seek to address this balance in varying ways:

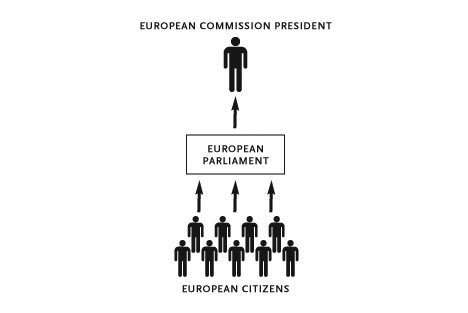

• A presidential system in which the citizens of Europe directly elect the President of the European Commission.

• A parliamentary system in which pan-European lists elect members of the European Parliament with the strongest representation/coalition of parties choosing the President of the Commission.

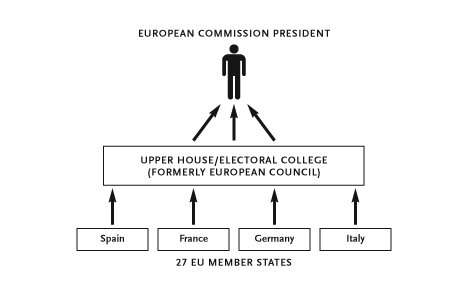

• Transforming the European Council into a “second chamber” (with seats allocated proportionately by nation-state population) that also serves as an electoral college that would choose the President of the Commission.

• Bridging sovereignty and democratic legitimacy through overlapping representation at the national and European level or involving national parliament leaders in common European budget oversight.

SHARING SOVEREIGNTY | “It was believed,” says former German foreign minister and Green leader Joschka Fischer, “that formalized rules—imposing mandatory limits on deficits, debt and inflation—would be enough. But this foundation of rules turned out to be an illusion: principles always need the support of power or they cannot withstand the test of reality. The eurozone, a confederation of sovereign states with a common currency and rules, is failing. Unless political power in Europe is Europeanized, with the current confederation evolving into a federation, the eurozone, and the EU with it, will disintegrate.”

Few today envision a vast transfer of sovereignty from the European nation-state to some bureaucratic Leviathan in Brussels. What most envision is a limited central government that only takes on those competencies European nations cannot themselves fulfill. Its role would only be to provide those common public goods beneficial to all European citizens but which are beyond the capacity of any individual state to provide.

Jacques Delors has made this point recently. “I have never been a federalist fundamentalist. If I use the formula ‘federation of nation states,’” despite its ambiguity, it is because I am anxious to propose elements of union within diversity. We should never neglect the nation as a factor of reference and as an element of motivation throughout history. Hence, a new architecture must be imagined and offered to the deliberation of the peoples of Europe.”

European Parliament President Martin Schulz, for example, has identified these limited zones of competence as finance, trade, the environment and immigration. Others would add transnational infrastructure as well as security and foreign policy to these public goods.

In this respect, a European Political Union would more closely resemble the Swiss Federation than the United States—a federation of plural identities that share in the provision of common public goods and the rules of fiscal responsibility required to sustain a single currency rather than one cultural and linguistic union where broad regulation and spending mandates emanate from a central government.

The EU should not become “a United States of Europe” in the end, but a “supranational sovereignty”—the accumulation of national sovereignties. In short, a federation of nation-states, as Delors says, instead of united states.

In such a federation, spending mandates, budgets and regulation beyond the kind of common public goods within the zones of competence identified by Schulz would remain with national legislatures, though necessarily supervised and monitored by a European Ministry of Finance so that imbalances among nation-states do not undermine the single currency.

Here, it is instructive to examine the differences between Europe and the United States in defining how and where sovereignty might be shared, and how and where it shouldn’t.

Nobel laureate Robert Mundell—the so-called intellectual father of the euro—offers the following comparison and suggests one innovative approach to how Europeans might share sovereignty through a Ministry of Finance.

“It was the ingenuity of the American founders at the Constitutional Convention (May to September 1787) that they were able to cut the Gordian knot on the question of sovereignty. The states wanted to be sovereign but federalists wanted sovereignty in the central state. The conventional wisdom of the late eighteenth century was that sovereignty could not be shared, and democracy was possible only in small republics; Rousseau had even said that the smaller the state the better. The Constitutional Convention provided for divided and overlapping sovereignties, in contrast to saying that sovereignty had to reside in one place.

The US was the first country to create a nation-sized democracy dividing sovereignty between the states and the central government. The powers not allocated to the central government were reserved for the states.

At first it might seem that this division of sovereignty might solve the fiscal problems of Europe. But the division of powers in the US was associated with the means of financing them. The central government had the responsibility for financing its mandates, and so did the states. But there was no arrangement for the central government to assume powers over state spending or deficits. What could be achieved—either by constitutional amendment or else quasi usurpation—was that the central government could assume for itself new functions like social security, income redistribution and medical entitlements that never existed when the constitution was set up.

The European system organizes welfare state spending at the nation-state level, whereas the American system achieves this at the federal level. General government expenditure in both the EU and EMU was slightly over 50 percent in 2010 of which social transfers accounted for 43 percent or 21 percent of GDP. If social transfers in Europe were shifted from the nation-state to the central state level, the weight of the central government in Europe’s GDP would be at over 20 percent—close to its weight in the US. Of course appropriate taxes would also have to be shifted from the nation-states to the central governments.

Under these conditions, the proposal for a European Minister of Finance, if given the powers equivalent to that of the Secretary of the Treasury of the US, would put European fiscal policy, from the standpoint of its control over spending, in the same positionas US fiscal policy. In Europe total government spending would be about equally divided between federal and nation-state level, whereas in the US state spending would be considerably smaller than federal spending.

I raise this issue not to propose such a shift in spending in Europe at the present time, but to make clear that the share of sovereignty is pretty straightforward when it is accompanied by a shift in the share of spending mandates.

But this is not the situation in Europe today. A shift of welfare-state spending from the nation-state to the federal level would involve a substantial redistribution of income from the richer to the poorer states. In the long run there may be much to be said for this redistribution on grounds of social solidarity, but it was not part of the bargain made for entry into either the EU or EMU. In any case, it would be unfair to impose the burden of this redistribution all at once on one generation.

If, as I assume, this shift of spending power to the central government is not politically feasible at the present time, we have to see what headway can be made with a shift of authority without the shift of spending mandates.

A natural model is the IMF with its 187 members including the seventeen EMU members. The IMF is an institution that imposes adjustment policies as a condition of its aid, and it has a multiplier effect because private-sector lenders (e.g., the Paris Club or London Club) often require compliance with IMF conditions as a prerequisite to lending or debt-rescheduling or forgiveness.

Suppose that the proposed Eurozone Minister of Finance (EMOF) were suddenly interposed between EMU members and the IMF. To abstract from possible differences in expertise let us suppose that the relevant IMF staff is seconded to the Euro Minister of Finance and that existing IMF policies are continued.

This arrangement would give power to the EMOF without diminution of sovereignty from the nation-states that has not already been given up to the IMF Board of Governors. But actually, the individual members of the Eurozone affected would have reclaimed some sovereignty because they have a larger stake in EMOF decisions than they have in the IMF decisions. The allocations of funds that would have been made by the IMF to their clients in the Eurozone, would now go through the EMOF.

Independent of an EMOF taking over some power from the IMF, there could be a ceding of sovereignty from the nation-states to a central government in exchange for better defenses against insolvency.”

German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble and their Christian Democratic Union (CDU) also envision a European Minister of Finance or a “Commissioner for Savings” to “monitor member states use of resources subject to a procedure of controlled debt reduction” who would have “the right to intervene in cases where the state fails to meet its obligations.”

Here, Notre Europe’s Yves Bertoncini makes some key observations about the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance that went into effect in late 2012. First, the compact symbolizes Europeans’ financial and economic interdependence; Second, it puts in place safeguards on the abuse of public accounts, but does not define their substance; Third, such fiscal discipline is not necessarily a synonym for austerity.

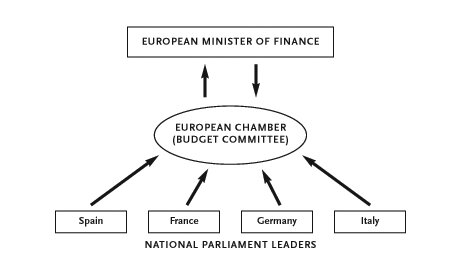

Other institutional mechanisms for sharing sovereignty, focusing on the fiscal responsibilities of European Parliamentarians, have been suggested by Joschka Fischer and Jürgen Habermas that would leverage the democratic legitimacy of the nation-state for an effective common European budget policy.

“Because there can be no fiscal union without a common budget policy, “ Fischer has written, “nothing can be decided without national parliaments. This means that a ‘European Chamber’—comprising national parliament leaders—is indispensable. Such a chamber could be an advisory body, with the national parliaments maintaining their competencies; later, on the basis of an intergovernmental treaty, it must become a real parliamentary control and decision-making body, made up of national parliaments’ delegated members.”

Similarly, Habermas has suggested that “certain members of the European Parliament at the same time hold seats in their respective national parliaments.” In this way, the legislator would, in effect, represent a dual sovereignty.

DEMOCRATIC LEGITIMACY OF EU INSTITUTIONS | The lack of legitimacy of European institutions has hindered their capacity to respond to the euro crisis, engendering a further erosion of allegiance to the vision of a European future. Critics have argued that inter-governmental agreements for austerity and debt relief so far are “post-democratic” and “neo-colonial.”

There are several key proposals to close the so-called “democratic deficit” that will enhance the democratic legitimacy of European institutions.

The CDU/Angela Merkel/Wolfgang Schäuble have proposed the following.

• The President of the European Commission is directly elected by the public. The “political unity of Europe needs a face,” says Schaeuble;

• The allocation of the European Parliament seats would be changed to “reflect the populations of the member states to a greater degree than hitherto”;

• The Parliament and Council would be able to initiate legislation;

• Countries “willing and able to move faster” toward integration may do so.

In its September report to the European Council, the Future of Europe Group also called for direct election of the European Commission president, a stronger Parliament that can initiate legislation, making the Council a “second chamber,” a banking union and transforming Europe’s bailout fund into a European Monetary Fund.

Tony Blair, the former British prime minister, also favors the direct election of the European Commission President as a way to “put a face on power and accountability to the public.”

Gerhard Schröder, the former German chancellor argues that:

• The European Commission must be further developed into a government elected by the European Parliament;

• The European Council should be transformed into an upper chamber with similar functions to the Bundesrat in Germany;

• The European Parliament must have increased powers and in the future it should be elected via pan-European party lists with top candidates for the post of president of the Commission.

For Martin Schulz, leader of the socialist group and president of the European Parliament, “a restart of European democracy” can take place within the existing Treaties by reforming “the EU institutions to mirror the distribution of power in the member states”—this is “the real democratic deficit”—combined with “a full right of initiative of the European Parliament” to directly propose legislation.

This reform would transform the “consensus machine” of the Parliament into “a place of dispute” where policies are democratically legitimated because initiated legislation will have been fully debated by elected representatives of the public.

To achieve “institutional clarity,” the Commission should act as the “European government,” the Parliament as the “first chamber” and the Council as “the second chamber.”

For Joschka Fischer the key task of “Europeanizing Europe” means transcending the “original sin of creating a supranational structure that lacked democratic legitimacy.”

As noted above, Fischer believes that the eurozone needs a government that can consist only of the respective heads of state and government—a development that has already started. And because there can be no fiscal union without a common budget policy, nothing can be decided without national parliaments. This means that a “European Chamber”—comprising national parliament leaders—is indispensable.

Such a chamber could be an advisory body, with the national parliaments maintaining their competencies; later, on the basis of an intergovernmental treaty, it must become a real parliamentary control and decision-making body, made up of national parliaments’ delegated members.”

The key issue for German philosopher Jürgen Habermas is how to find the right combination of a “Europe of nation-states” with a “Europe of citizens.”

We have seen many more or less conventional alternatives for strengthening the European Parliament, establishing an effective and legitimate executive, and creating a democratically accountable Court of Justice.

These proposals do not exhaust the range of imaginative options. The core problem of Europe is that it must be a federation of nation-states that needs to preserve their integrity by occupying a much more influential position than the constituent elements of a federal state normally do.

The intergovernmental element of negotiation between former nation-states will remain strong. Compared with the presidential regime of the USA, a European Union of nation-states would have to display the following general features:

• A Parliament that would resemble the Congress in some respects (a similar division of powers and, compared with the European parliamentary systems, relatively weak political parties);

• A legislative “chamber of nations” that would have more competencies than the American Senate, and a Commission that would be much less powerful than the White House (thus splitting the classical functions of a strong Presidency between the two);

• A European Court that would be as influential as the Supreme Court for similar reasons (the regulatory complexity of an enlarged and socially diversified Union would require detailed interpretation of a principled constitution, cutting short the jungle of existing treaties).

Further consideration: It would help to overcome the legitimation deficit, and to strengthen the connections between the federal legislature and national arenas, either if certain members of the European Parliament at the same time held seats in their respective national parliaments, or if the largely neglected Conference of European Affairs Committee (which hasmet twice a year since 1989) could reanimate horizontal debate between national parliaments and so help to prompt a re-parliamentarization of European politics.

Are there alternative modes of legitimation too? The approach labelled “comitology” attributes legitimating merits to the deliberative politics of the great number of committees working in support of the Commission. But here there is a deficit on the output as well as input side, since federal legislation is implemented only through national, regional and local authorities. To meet this problem, some have suggested transforming the present Committee of Regions into a chamber that would give sub-national state actors a stronger influence on EU policies, and thereby facilitate the enforcement of European law on the ground.

Nobel laureate Robert Mundell has offered a detailed proposal for the evolution of the EU institutions in Brussels.

The main institutions are:

• The Commission

• The European Council

• The European Parliament

• The Electorate.

What Europe needs is:

• An Executive Power

• An Upper Chamber or Senate that serves as the Electoral College

• A Lower Chamber or Assembly

• The Electorate

The Commission could be turned into the Executive Power with its Cabinet/Commissioners appointed by the President. The President would be appointed by the Electoral College.

The European Council representing the Governments could be turned into the Upper Chamber or Senate and Electoral College with the Vice-President as its Chairman.

The European Parliament could serve as the Lower Chamber.

The alternative to an Electoral College would be the general election of the President. My own view is that in an area as diverse and heterogeneous as Europe it would be better to elect the President and Vice-President through an Electoral College by majority vote. The extra attention given to the general electors of the Electoral College would create a level of excitement and interest far above that of a Europe-wide majority vote.

The Executive would nominate the Judiciary with approval by the Senate. The Executive makes treaties subject to ratification by the upper chamber, and it proposes bills subject to ratification by both chambers.

The President is the commander in chief with a special protocol for British and French nuclear weapons. The Lower House or Assembly has around 500 deputies distributed among countries in proportion to population. Budget proposals initiated in the lower house must be accompanied by finance solutions.

The Council of Ministers is expanded to the upper house and given certain special powers. In this model, with a total of 128 Senators, countries with a population of: over 80 million would have 12 Senators; 65 to 80 million would have 10; 50 to 65 million would have 9; 35 to 50 million would have 8; and so on. You would then have a framework for division which isn’t as rigid as that which determines the composition of the US Senate and it would be a correction for disparities that exist in the Senate, such as having 2 Senators for Maryland, with a population of less than a million people, and an equal number for California with 40 million people.

In the Electoral College, which votes for the President and the Vice President, each nation has electoral votes equal to the number of Senators and representatives in Congress. The presidential candidates with the majority of votes get the entire vote of the nation-state.

The European Commission is a very successful institution. It is necessary to preserve some of its competence as a technical bureaucracy. Vice Ministers would be drawn from the Civil Service, but Ministers would be members of the Cabinet appointed by the President with the approval of the Senate.

GETTING FROM HERE TO THERE | The time is right for a European Convention to chart the course forward, according to Gerhard Schröder:

“The time is now ripe to move forward through a European Convention. A European Convention is part of a process of renewal that leads to Europe-wide discussions.

In the past, for example, Germany initiated the convention to develop a European Charter of Fundamental Rights and a Constitution for Europe. The debates were about all the same issues we need to discuss now in this new context: democratization, accessibility and clarification of responsibilities; the delimitation of powers between the Union and member states.

Unfortunately, the Constitution for Europe came to nothing, but many of its elements are present in the Treaty of Lisbon. It is now time for a core group of states ready for integration to initiate a new convention for the future of Europe.”

Others suggest that the Lisbon Treaty and intergovernmental treaties can pave the way. Schröder, like the CDU, believes that “those willing and able to move faster” toward integration should do so, with the rest of Europe in various stages of “association” until they are ready to join.

Joschka Fischer also believes that, “like it or not, the eurozone will have to act as the avant-garde of the EU.”

The CDU envisions that the changes necessary to share sovereignty and close the democratic deficit may begin with intergovernmental arrangements and then later be entered into the European Treaties. Barroso also believes the shift could begin under the current EU treaties “but can only be completed with a new treaty”.

Jacques Delors argues that a “genuine opportunity” arises with the European Parliament elections in 2014. “[Institutional] clarification could come from the fact that on this occasion, European political parties could override national parties. Each European party could agree on a project for tommorrow’s Europe. This would also lead to precision: Who does what? What about subsdiarity?”

EUROPE IN A GLOBALIZED WORLD: COMPETITIVE CONVERGENCE FOR JOBS AND OPPORTUNITY | For Europe to achieve high-employment prosperity in the future—no less continue to afford its welfare state in the face of increasing competition from the “rising rest” and the demographic challenge of an aging and shrinking population—it will have to become more globally competitive.

Everyone agrees that to do so the fiscal and competitive conditions of the various European states must move toward convergence in order to adjust the imbalances that have destabilized the eurozone. Only then can Europe as a whole becomes a strong enough player in the world economy to fully reap the benefits of globalization.

But, as with the general idea of a European political union, there is more agreement on the goal than consensus on what that actually means and how to get there.

Marek Belka, the former Polish prime minister and current President of the National Bank of Poland, has offered a clear-minded framework for thinking about the issue:

Preserving a common currency among sovereign nations has proven very difficult, as we have all become painfully aware. It isn’t just a matter of maintaining fiscal discipline, but of preserving the international competitiveness of individual countries.

Not all countries can be like Germany, and not all should be the world’s leading exporter in high-tech products. Nevertheless, each country must somehow be attractive to others. In other words, it is important to ensure that the individual countries do not drift even further apart. In short, in a European zone with a common currency, not all countries need to show balanced trade and current accounts. Some may be food suppliers, while others supply luxury goods, and others provide travel services for tourists over the long term. Spaniards should remain Spanish, Germans German, Greeks Greek and Poles Polish.

In being themselves, however, individual countries cannot lose their trade-in value for others. We cannot succeed in preserving the monetary union if individual members have nothing to offer but cheap labor, or worse, if they mutate into permanent welfare recipients.

These are obvious truths. What is not as evident, however, is the reciprocal relationship between economic competitiveness and political structural reforms. We have always recognized the significance of these problems in the European Union, at least in a formal way. Remember the Lisbon 2010 agenda? At the time, ambitious guidelines were developed to foster the modernization of individual countries, and as a guarantee of the global leadership of the entire EU. In reality, no one took the Lisbon agenda seriously because people believed that countries that did not pursue proper structural policy would ultimately lose their European market share and would be displaced by others.

However, the current crisis revealed that the “spill over effect’ was detrimental to the remaining members of the community when individual EU member states did not take sufficient steps to safeguard the competitiveness of their economies.

Only in recent months have we experienced quite strikingly that Mario Monti’s structural reforms in Italy are of almost equal importance to other Europeans as they are to Italians. Today, structural policies, like fiscal policies, are no longer solely the business of the euro countries.

There are those in Europe who complain that Germany is too strong a competitor, that others cannot keep up, and that this could even lead to the destabilization of the common currency. But what would happen to the European economy if it didn’t have this German engine? Wouldn’t the problems of excessive debt in public and private budgets be equally painful? Would anyone in the world believe in the euro anymore if this German engine didn’t exist? The truth is that the European Union would become a marginal zone in the global economy.

We shouldn’t complain about Germany’s globally competitive stature. But we also shouldn’t try to sketch out the future EU as if it consisted of nothing but copies of the German economy. Each country has to develop its own strengths. This should be done consistently, with the recognition that it isn’t just individual countries, but also other EU member states that suffer the consequences in the event of failure.

We’re all in the same boat, which means that today’s economic and social policies must come under rigorous scrutiny and coordination by the EU. This may sound like a substantial loss of national sovereignty. Will Europeans endure or even tolerate this?

To answer this question, I’d like to cite the example of Poland in the 1990s. In the context of its accession to the European Union, we had to adjust legal requirements in almost every sphere of EU standards. This meant adjusting the way we lived. Wasn’t that a significant intrusion into national sovereignty? Since it was a success, no one in Poland complained about the loss of national sovereignty and today, Poles are probably the most enthusiastic about the EU.

This suggests that the problem isn’t sovereignty, it’s the need to know our goals and whether we are willing to work towards these goals together. Are we aware of the risks, are we aware of our shared current and future European interests? This is the biggest challenge for Europeans right now.

Pasal Lamy, who heads the World Trade Organization and is honorary chair of Notre Europe, has reinforced the point made by Marek Belka that the global competitiveness of Europe depends on the internal policies of individual states:

Europe enjoys comparative advantages that ought to allow it to find its full place in the global economy. If we accept the idea that an improvement in its integration into international trade depends first and foremost on its internal policies, then we need to go back to the basic problem, which is a problem of excessively weak economic growth in Europe. That was true before the euro crisis, when the European Union’s potential for growth hovered around the 2 percent to 2.5 percent mark, but since the start of the crisis that potential for growth has decreased by half.

On a global scale, Europe is an island of prosperity and well-being thanks to a welfare

system which is of unquestioned quality, yet whose sustainability depends on significant growth both in the economy and in the population. However, Europe has a problem in both of those spheres.

A well-known solution to its demographic problem would involve falling back on immigration, but it is difficult to envisage such a solution being adopted in the short term on account of the positions espoused by Europe’s political forces on the issue. It would also be opportune to make it easier for people to reconcile their personal and professional lives, and to remove obstacles standing in the way of an increase in the birth rate, which has dropped to critical levels in European countries where the generational turnover is no longer guaranteed—although there are a few exceptions, and one of them is France.

Where potential for growth is concerned, the crisis has highlighted difficulties incurred through the problem of excessive debt. The only way to keep the social security system going without significant demographic growth is by increasing the economic growth rate. Yet it is difficult to impart a fresh boost to the growth of an economy whose potential for such growth has been damaged by the crisis and which is having to cope with the burden of

deleveraging. Yet therein lies the whole issue: it is a matter of boosting potential for growth by 1 or 1.5 percentage points in order to be able to continue funding the European welfare system and to pay down the debt that has built up to date.

The reforms required to achieve this goal and to make the best of Europe’s comparative advantages are long-term reforms primarily regarding its education, training and innovation system. It is in that sphere that the difference between countries and continents is going to be seen.

A population’s level of education is the single variable that has best evinced differences in economic growth and success worldwide over the past 40 or 50 years. But public education and innovation policies can have an impact only in the medium and longer terms. So in view of that, how can we stimulate growth in the short term? It is a matter of devising measures whose impact can be felt at once.

We may find an answer to that question on the labor market, yet we have to combine fiscal and budgetary measures in order not to reduce productive public expenditure, whichhas a driving effect on the economy, and to avoid any rise in manufacturing costs so that we can protect our price competitiveness.

?Finally, monetary policy can also serve as a short-term lever for action. According to the Bruegel think tank, there is a way of managing the inflation differential within Europe intelligently so as to restore part of the competitiveness that is missing in the south. Inflation at 2.5 percent to 3.0 percent in northern Europe, coupled with lower inflation—at, say, 1.0 percent—in southern Europe would gradually allow countries that cannot devalue their currency to recover, to some extent at least, the price competitiveness they lack.

In sum, Europe’s dearth of price competitiveness and of “non-price competitiveness” must be the target of future public policies, which will give Europe the means to benefit from the comparative advantages that it should have. Education, training and innovation policies, the meticulous management of intra-Community inflation, and greater fluidity in the labor market are the pillars of a courageous reform equal to Europe’s legitimate ambitions in an increasingly competitive world.

Germany’s globally competitive stature did not emerge by accident, but was the result of precisely the kind of internal structural reforms recommended by Lamy. Gerhard Schröder, who was chancellor when the reforms were initiated, has summarized the policies and their results:

In the last few years Germany has managed to reduce the number of unemployed by around 40 percent while at the same time raising exports by around 50 percent despite the mounting global financial crisis.

So what did we do? My reform program, Agenda 2010, saw Germany respond to two challenges: globalization and demographic changes in German society.

We changed areas of the welfare system, in particular health insurance, pension and unemployment security. We made them more flexible and placed greater emphasis on the responsibility of the individual in keeping costs down.

Also, Germany’s short-time working program played an important role, where the state now shares the costs with industry to keep skilled workers on the payroll during economic downturns, thus enabling them to scale up quickly when the economy picks up.

For the German welfare state, these steps marked a paradigm shift that many believed would carve away hard-earned benefits. In fact, we were able to strengthen the system by making Germany globally competitive and ensuring that benefits remained affordable for our aging population. At the same time, we raised expenditures in education, research and innovation.

All this gave a further boost to German industrial base. Implementing these reforms was politically challenging—they cost me my job—but the result has shown it was worth it: Germany is now the best situated of all European economies. France, Spain, Italy, Great Britain and others now have to catch up with this reform process, but under much more difficult conditions.

How, then, can Europe as a whole head down the same path through policies that must be implemented within the internal political environments of individual nation states?

For pro-federalists like Guy Verhofstadt, Jacques Delors and the former Italian prime minister Romano Prodi, aligning European states more closely on such issues as wage levels, the social contract or tax rates should be the task of the European Commission—which represents all 27 members of the EU—rather than through “intergovernmental treaties” inevitably dominated by the larger states, France and Germany—mostly Germany.

To move toward convergence over the long haul, the Commission, in their view, should set the targets for all of Europe.

Given the diversity among Europe’s economies we do not envisage a one-size-fits-all policy. Rather, we need a clear and united path to convergence on an agreed set of policy measures. Presenting proposals to this end should be the task of the Commission.

For each proposed measure the Commission should establish—with the agreement of the member states and the European Parliament—a range of standards or goals, within which member states are expected to converge by a given date—for example on the retirement age and a common corporate tax base. The same would be true of R&D investment levels, and wage to productivity ratios.

Progress would have to be regularly monitored, again by the Commission, which should have the power to apply pressure (and ultimately sanctions) for non-compliance, just as it does for breaches of competition rules or infringements of internal market legislation.

|